This 7-part series has been first published on Sustainable Brands between late January and early March 2016 as a 6-part series and a follow-up by Bill Baue, co-founder of Convetit and the Sustainability Context Group. It captures the essence of my thinking I was able to gather through the extraordinary work of the Reporting 3.0 Platform, GISR and the ThriveAbility Foundation in 2015. What came out is a structure that I called a ‘new impetus embracing purpose, success and scalability for thriving organizations’. I am reposting the original 6 parts here and add a part #7 with reflections of others. This is part 3/7.

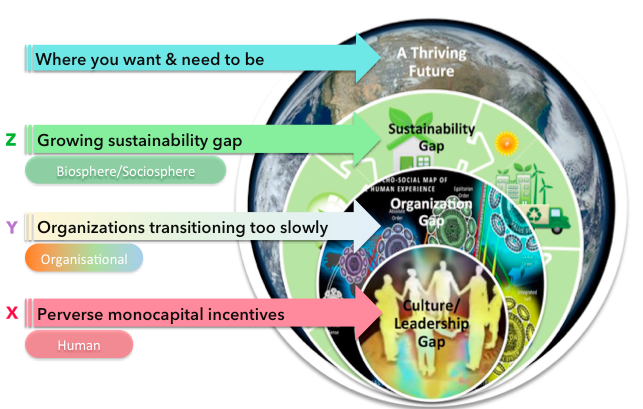

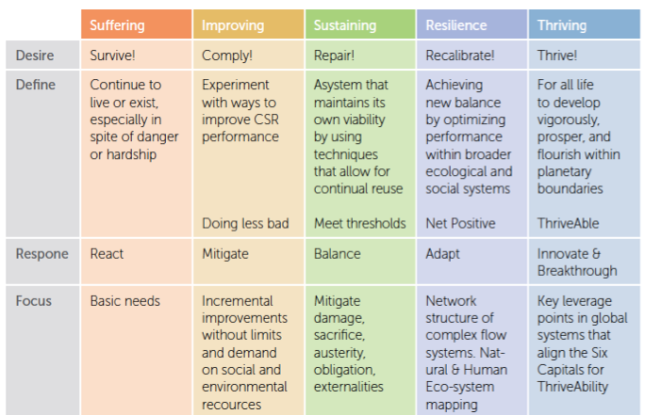

In Part One of this series, Diagram 1 showed an overview of the three main areas of the proposed change need for integral thinking and true materiality; Part Two explained why we need this new impetus. Part Three now tackles the upper section of the triangle – the need for chrystalizing purpose to better show connectness to the problems that need to be solved in interrelated ways.

Diagram 3: Integral thinking and true materiality need a renewed focus on the purpose of the organization and connectedness to the economy we want to live in.

Diagram 3: Integral thinking and true materiality need a renewed focus on the purpose of the organization and connectedness to the economy we want to live in.

It has been interesting to see how the discussion about ‚the purpose’ of an organization or an economy has moved into the forefront in the last 1-2 years. The 2015 numbers of the Global Footprint Network (GFN) or from UNDESA on population, consumerism and the environment [insert link] are just telling one striking story: as a species, we humans are on a slow death path.

The fact that the ‚human’ role in sustainability now gets back into the focus simply shows that it dawns on us that we forgot to take people on board of the sustainability journey, in companies as well as in private circumstances. Sustainability is not exciting for the majority of human beings. We see constant shoulderclapping about reports in which we are told how much less bad a reporting entity became, without any ‚North Star’ that could tell us what is ‚minimally good enough’, or what would lead to an envisioned future beyond just having a ‚zero negative impact’; this was sucked up by our frugality of installing sustainability departments that took care of policies, management systems, reporting and assurance. The ‚three gap problem’ as discussed in Part Two of this series led to a reduced understanding of sustainability in which essential aspects of sustainability like ‚people, planet and prosperity’ became ‚people, planet and profit’ and intergenerational equity fell by the wayside.

In consequence, Sustainability Context still remains the most neglected Content Principle of any GRI-based sustainability report. Seldom does a reader understand the ‚world view’ of a company, its leadership advocation to change the economic system towards serving a green & inclusive economy, and how the product & service spectrum offered makes a positive contribution (instead of less negative impact), alone or in collaboration / co-creation with others.

It is amazing to see how disconnected sustainability or integrated reports are with ‚the whole’ which we are contributing to (or not). Reporters typically claim it’s too complex to envision a different economic model, exploring a new level playing field in which market mechanisms can automatically work towards an aimed-at state of being regenerative and inclusive. Isn’t that what scenario analysis was invented for?

We developed our current economic model as one set of conventions, and it is up to us to change that for the better. Haven’t we already decided to aim for a green & inclusive economy at Rio+20 in 2012? So where are we with that? There are indeed some positive prompters here:

- There is a whole set of macro datasets that show the ‚global pulse’ of our continued negative pathway, which means a better understanding of the interconnectedness of our doing and its effects on the planet is more and more possible. Various IT networks, data providers and technology firms work on making ‚the whole’ visible, up to artificial intelligence (AI) approaches (see a variety of these in the Reporting 3.0 2015 conference report, http://www.reporting3.org). The main issue here is to translate that into data clusters that corporations can use for their ‚micro-macro’ impact interpretation.

- A variety of companies and development organizations work with the idea of Creating Shared Value (CSV) as proposed and vividly defended by Porter and Kramer for years. While definitely a good learning approach, CSV doesn’t yet prove to be able to either move the concept beyond the ‚feelgood’ areas of collaboration and co-creation; the nasty issues aren’t really solvable since they need new ‚rules of the game’, a normative approach to global change. And secondly, CSV aims at optimizing within an existent frame of economic system boundaries. We won’t get to a sustainable or regenerative economy without also tackling those economic system boundaries to create new level playing fields in which industries can transform. Porter and Kramer, it seems, remain in the 1990s thinking of enlarging competitive advantage with creating (extra) shared value.

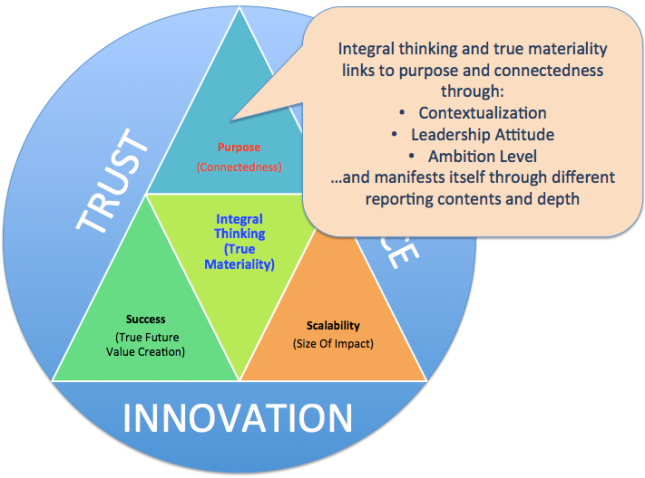

- The Sustainable Development Goals are an interim step towards learning to understand thresholds in a context-based sense, leading to less-bad impact, probably a planet of ‚Zeronauts’ (to stress John Elkington’s brilliant book from 2012). The translation to apply and measure contributions in the corporate world, in local and regional circumstances as well as globally, is still to be developed. A plethora of initiatives are underway to find out, and hopefully it will be a training area to explore the possibility of thriveable, gross positive impact as the greatest innovation boost ever. Each company needs to define where they stay in the continuum that the ThriveAbility Foundation has offered, see the following diagram:

Diagram 4: The strategy continuum to assess a company’s position in a world that needs to leapfrog from surviving to thriving (Source: A Leader’s Guide to ThriveAbility, page 18).

Diagram 4: The strategy continuum to assess a company’s position in a world that needs to leapfrog from surviving to thriving (Source: A Leader’s Guide to ThriveAbility, page 18).

- Kate Raworth’s ‚Doughnut’ model, showing environmental ceilings and social floors, has given us a 2-dimensional picture of interconnectedness, but only good enough to get us from suffering to struggling – it misses the ‚operating system’ to create real thriving. This model needs adaptation to become 3-dimensional, adding the component of human transformation to accelerate positive change. This is what the ThriveAbility Foundation recommends to get us from stage 1-3 of the above diagram to stages 4 and 5, and in consequence appeals to a change from an ‚ESG Push’ towards a ‚GSE Pull’, addressing authority, decision-making and accountability in one stringent approach. This needs leadership in ways that until now only a Ray Anderson (Interface), Paul Polman (Unilever), Sir Ian Cheshire (ex-Kingfisher) and some other corporate leaders have shown. Only through this advocacy will we get to economic system boundaries change addressing the ‚macro-micro change area’, mainly though the combined integration of external effects into cost accounting, translation into pricing mechanisms, and counterbalancing those effects by a drastically changed tax and subsidies regime on a global scale. The work of Trucost, the True Price Foundation, Ex’tax and others in this area are therefore essential to get this masterplan done over time, together.

So, imagine a sustainability and/or integrated report that showcases a reporting organization’s contribution through a chapter on purpose and connectedness. What would a reader expect to see answered? The below are examples of what I personally would find substantial in that area.

On Contextualization:

- Does the company have a ‘World View’ and a long(er)-term idea of positioning in the continuum from ‘Compliance’ to ‘Thriving’ when it comes to impacts and outcomes across the multiple capitals? Where does it want to be in the future?

- Is there one strategy, or does the company have a separate sustainability strategy (which should be avoided, as it signals sustainability as a side issue)?

- Is the corporate strategy based on affecting the root causes of global non-sustainability, or is the strategy just based on curing symptoms of non-sustainability (like the majority of companies do at this moment)?

- Are there various scenarios in which the company is testing its possibilities to impact and gets addional insight into its long-term positioning?

On Leadership:

- Is the socio-cultural leadership gap addressed (part of the three-gap problem)?

- Are company leaders assessing the transformation blockages in the sustainability gap (also part of the three-gap problem)?

- How is sustainability visible in the organizational hierarchy? Is sustainability integrated in strategy and governance so that the sustainability team could veto non-sustainable corporate decisions?

- To what extent is the leadership group aware about a responsibility for sustainability above and beyond the legal construct of the organization?

- What does the company contribute to asks or campaigns to change the unsustainable boundaries of our current economic system, e.g. trade barriers, unsustainable subsidies, political lobbying, testing new ‘level playing fields’ through the combination of true costing, true pricing, true taxation?

On Ambition Level:

- What’s the company’s view on growth? How does it differentiate sustainable from non-sustainable growth?

- How does the company define its ambition level and how are short-term targets derived from succeeding its long-term ambition level (e.g. through back-casting)?

- How are all employees included in defining the purpose and connectedness of the corporate strategy to sustainability?

- How does the company differentiate efficiency gains, productivity gains and their respective rebound effects vis-à-vis the need for sustainable innovation?

It is these questions that build the ‚glue’ and segway into the vision of performance beyond just doing the minimum needed. It would add to the idea that current approaches don’t add up altogether and that technology alone won’t cut anything without the humans on board. This is tough work in hierarchical structures and even tougher in multinational companies. But it honestly the only way we can deliver. It is time for new conventions.