It’s the week after the GRI Conference, the week when we attendees all return to our desks and reflect what we heard and learned. Clearly, GRI has set important steps, has changed its strategy towards becoming a standard setter, and has entered the digital age in earnest, finally. And yes, it was the networking that was valuable and to me it felt like a family gathering. There is no doubt about that. But are we convinced? Is this the big next thing?

Let me take you on my personal journey, and note my background with GRI from 1998 onwards, including time as a GRI staff member from 2002 until 2008. I am probably one of the very few that have been actively involved in developing all 4 generations of the GRI Guidelines. My feelings about GRI come deep from the heart, I sometimes joke about GRI as being a child going through its childhood and puberty, and now leaving home to truly build a life on its own, exploring new relationships, independent from the family’s own past. I’d like to present my thoughts in three sections:

Atmospheric distortions

In the run up to the conference I spoke to many people that I suspected going to GRI’s conference. I learnt that many of them decided not to go this year. When asking why, the answers were quite mixed, but they addressed various issues, and this continued in conversations at the conference as well:

- The glamour is gone: earlier conferences had highlights that were missing this time. GRI had Al Gore, Queen Rania of Jordan, Michael Porter and BBC news anchors in the past. Seems like these ‚sustainability celebrities’ are indeed attracting numbers of participants and GRI might have purposefully decided not to approach such people this time, for various (good) reasons.

- GRI’s communication about the new strategy, the new GOLD model of participation, the ‚exclusive clubs’ (Leader’s Group, Technology Collaboration, certified GRI practitioner process) isn’t yet resonating well with many, taking into account that most reporting organizations are also part of minimally half a dozen and up to a dozen other initiatives and networks. It all becomes complicated and hard to follow. Many out there who I talked to were surprised not to be ‚Organizational Stakeholders’ any more.

- A feeling of cold commercialization of what was supposed to be a community that embraced its members, involved its stakeholders for a common purpose (and I’m not even touching the pricing strategy for the conference, especially the huge amount of ‚exclusive’ sessions and to-be-paid-for masterclasses). The true multi-stakeholder nature has moved a bit into the background. A new set of standards is now presented to the world, designed by the GRI staff and the GSSB. ‚Hold on a minute’, I heard often: ‚wasn’t there a working group process designing this? There suddenly is a public comment period about something I wasn’t even aware would come?’ Of course, just restructuring G4 into a set of standards doesn’t need a full multi-stakeholder process I said, but it wasn’t clear to many and a sign that information overload takes its toll.

- The notion that GRI’s conferences tend to lose focus on the reporting aspect. Many sessions are broad discussions about sustainability with little rigor or facilitator focus to bring it back to reporting and/or disclosure, at least at the end of the sessions. Is it helpful to have sessions about who to trust more (governments or NGOs or corporations) when all of them have a role to play in adding and consuming data? While I thought this year’s conference was more focused when looking at the session’s titles, the discussions themselves often remained less focused.

Summing up this part, the words of a former high level representative of GRI’s governance bodies still rings in my ears, saying ‚GRI is losing its soul!’. Indeed, some say GRI starts to copy/paste what SASB has been doing in past years, has a strong bias with financial market players (although hardly present at the conference), is very North America and Europe focused, and communicates less with its (former) community. My own experience is that there’s now at least as much talk in conferences why not to follow GRI any more as there is talk to position it in the overall reporting regime, including IIRC’s integrated reporting approach, SASB’s industry specific disclosures, the EU Directive’s requirements, the rating organization’s questionnaires and the requirements of stock exchanges. I think we are at the point where GRI’s growing number of younger staff starts to forget about the roots of the organization, where the different departments within GRI have their own means of communication and that indeed some ‚soul searching’ would be recommendable. If 1.200 participants (including 200 speakers and GRI staff) mean ¼ less participants at the confernce (noted by many), it points to some homework to be done in re-emphasizing the true purpose of GRI. To many it isn’t so clear any more, before and after the conference, at least for those who went.

Necessities

A lot of what GRI presented at the conference makes a lot of sense to me. The move from Guidelines to standards helps to generate a more constant work rhythm for the GRI Secretariat, creates the ability to make changes to individual standards, given the advances of science or technology, becoming more strict in defining requirements besides recommendations and guidance. This could strengthen stock exchange requirements, legal requirements, governance aspects, assurance processes and simply enhance additional clarity away from blurry descriptions. It would also hopefully reveal still existing greenwashing in reports.

GRI finally also moved into the world of digital technology and data. The Technology Consortium – as was announced at the conference – will be broadened through the ‚Digital Reporting Alliance’, called to be the ‚vanguard of the next phase of sustainability reporting’. I agree with the need to ‚liberate’ data from pdf’s and use new technology to make the data available for everyone’s use. In the end, it’s the impact that data make, so the number of sustainability reports per se doesn’t really define the success of sustainability reporting. Rather, it’s the transformational capacity these data entail; it’s what the data reveals about those affected by corporate actions and how companies and their stakeholders alike can use these data to drive such transformation. This needs new approaches and open source platforms, like WikiRate, that have the ability to not only liberate data, but also to democratise the accuracy and use of data and put them into context through open data indicator development. It holds the power that an emission scandal like Volkswagen could be detected before it actually goes through the roof. eRevalue, a narrative screening ‚vacuum cleaner’ data service has shown that disclosure of emission data has gone down in the majority of corporate sustainability reports of automotive companies in the last years, except Ford Motor Company. Look at what has come out over the last half year and who is now accused of using emission control software and who is not: Ford Motor Company is amongst the few in the latter category. The power of data is just at the beginning of an explosion, so GRI’s aim to support data liberation through partnerships is important. Various sessions during the conference focused on data and transparancy.

The uncovered to-do’s

GRI’s conference took place at an important moment in time. After COP21 in Paris and all the follow-up happening to get countries adopting the agreement, and after the SDGs got accepted and are now waiting for the processes to best implement them internationally and country-by-country, GRI looked at these from the perspective of making necessary links (GRI, WBCSD and UN GC already published the SDG Compass last year). Of course GRI was also involved in the preparations of both these events, within the limit of its mandate. These themes were of course captured in important sessions at the conference.

But what struck me most was what was not discussed, and given the fact that about 90% of the global multinationals are still not reporting on their sustainability achievements (partially based on the fact that a huge amount of these companies are privately held and still sneak out of mandatory reporting requirements), we are still far from mainstream. As the conference subtitle was ‚shaping reporting for the next 20 years’ GRI missed addressing a list of things that will have at least as much influence on the future success of GRI than the steps now taken. Here are my top 5:

- As sustainability reporting sort of goes with the flow and – while mentioned in the Guidelines – chronically forgets about sustainability context, we remain at an incremental stage of disclosure. We are missing the benchmarks of getting closer to the real deal: disclosing when a company can call itself a ‚sustainable company’. While environmental ceilings and social floors are known, global footprints are defined up to local level, and more data about the condition of the world are available than company-internal data, the discussion around context was close to absent. Just a glimpse of that came up in a session about linking corporate data with national statistics data on the SDGs. I highly doubt that the national statistics offices will excite corporations to make the necessary data links and suddenly push innovation.

- Redesigning dislosures based on a more capitals-based approach. The basic assumptiom of building accounts around a ‚systemic contribution’ to society will need to answer the question about value creation. There isn’t any better litmus test than to disclose in how far financial capital has been built on the back of any other capital. This doesn’t mean total monetization of all capitals, but starting to discuss conventions and directions on how to count and account, working towards qualities such as the ‚Total Contribution’ concept of the Crown Estate in the UK. Realizing that net positive and gross positive approaches are possible beyond what is now seen as sustainable (doing no harm) seem to be so far away from mainstream that GRI doesn’t give these truly commendable approaches a stage. As such the needed collaboration with accountants – not very active in rethinking accounting from throughput to circular – isn’t a programmatic area of GRI, but will be the Achilles heel of the purpose of sustainability disclosure if it wants to stand the litmus test.

- The word ‚innovation’ was high up on the agenda. The opening session carried a set of three innovative entrepreneurs (potentially none of them producing a sustainability report), that aimed to somehow make a sort of connection to innovation, but in the proceedings it boiled down to the forthcoming standards and data aspects that seemed to be the only real news in reporting. Of course, communication, XBRL (if ever used mandatory) and open source data can make a big difference, but it’s the combination with data that are not yet in GRI’s terrain that can empower stakeholders to new qualities of dialog (at this moment often in a degenerating stage due to boring processes) that will potentially revitalize dialog, meaning empowering stakeholders to be well informed to talk to corporations at the same eye-level.

- The systemic component of how to create a longer term roadmap involving macro, meso and micro level, defining a truly serving purpose of reporting, linked with innovations in accounting, data management and new business model reporting demands, was little to non existing. The conference emphasized once more the need to go beyond the reporting standard setting world to overcome the inherent problem of standard setting – a too short scope to be able to deliver on future-ready reporting. The Reporting 3.0 Platform, now in its 4th year of existence (reporting3.org), has recently announced the ‚Blueprint Projects’, a set of 4 projects that develop and cross-pollinate the different necessary constituencies in the reporting landscape: reporting (clarifying the principles and serving function of reporting that truly supports a green & inclusive economy), accounting (based on a multi-capitals approach), data (taking into account the internal and external data sources to deliver on the litmus test question of being sustainable), and new business models (and their demands to disclose in principal ‚handprint’). Will we be able to deliver on reporting ‚for the next 20 years’ without any of these areas fully embedded?

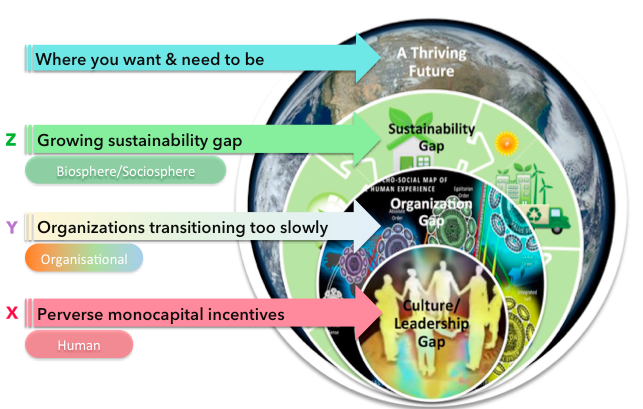

- Lastly, are we actually asking the right questions? The predominant focus on ‚footprint’ isn’t exciting for the majority of companies on this planet. We totally forget forging ‚handprint’ information. Instead of not doing harm, doing good isn’t structured in sustainability reporting, so all reporters are asked to figure that out themselves. The new circular, sharing, collaborative businesses are bluntly absent from the disclosure through existing standards, but it would be them to learn most from. Also, there are no data and benchmarks that would aim to describe the organizational transformation capabilities and socio-cultural leadership capabilities of an organization, adding to the litmus test question described above. We’re not even touching the sustainability context gap in its totality, and we’re missing two major components of necessary disclosure (see the work of the ThriveAbility Foundation to learn more about that, thriveability.zone).

Summing up this last headline, GRI needs to of course balance the needs of the mainstream and take reporting organizations from where they are at to where they should be, but the conference didn’t deliver on a good sketch of ‚the next 20 years’, embedding the SDGs into disclosure and liberating the data seemed to be the maximum presentable to conference participants.

Of course, one can argue that first things come first and that we are expecting too much. I know so very well from my own GRI past that ‘globally applicable and globally acceptable’ was and is the mantra for disclosure items to be added to GRI’s list. There will be another 5 GRI conferences until 2030 where more of this could be discussed, but do we have the time to wait? The absence of at least a statement of what’s still needed to deliver on the mission of GRI and a roadmap that offers a back-casting of the next steps for the next couple of years, concerned many of us at the conference. Now was the time to address and embed these necessary enhancements, but it seems we have to wait until the 2019 edition of the conference to add these points to the reporting matrix. The least we can do is to continue to work with GRI to show what is possible until then.

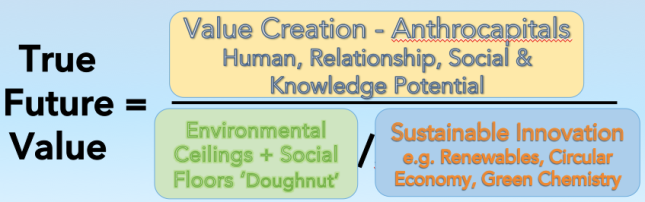

Diagram 6: High-level formula for deriving at ‘True Future Value’; a more detailed version with all variables can be sent by the author on request.

Diagram 6: High-level formula for deriving at ‘True Future Value’; a more detailed version with all variables can be sent by the author on request.

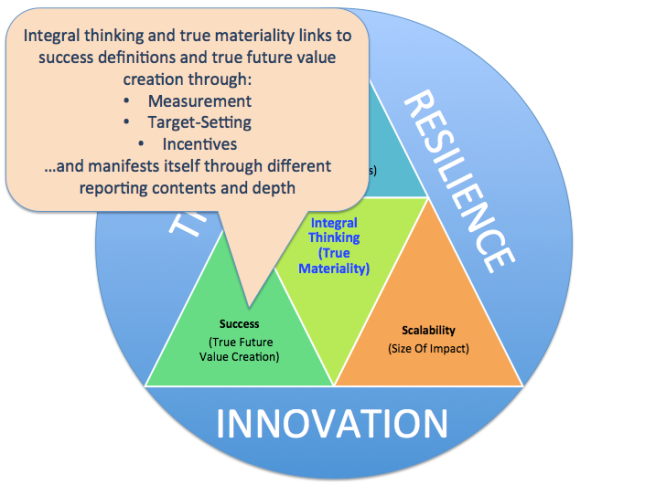

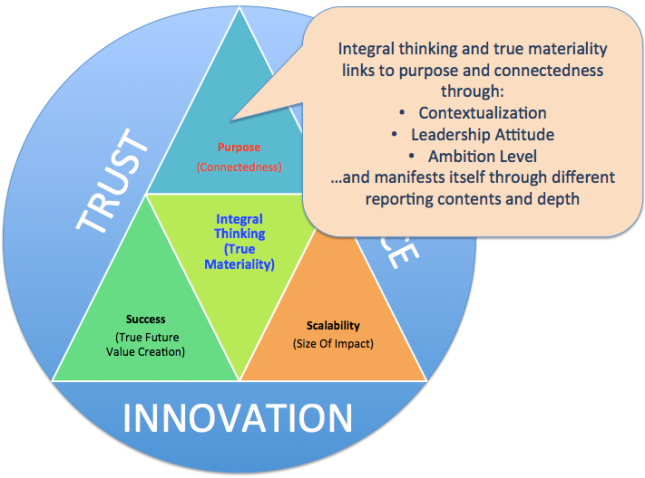

Diagram 3: Integral thinking and true materiality need a renewed focus on the purpose of the organization and connectedness to the economy we want to live in.

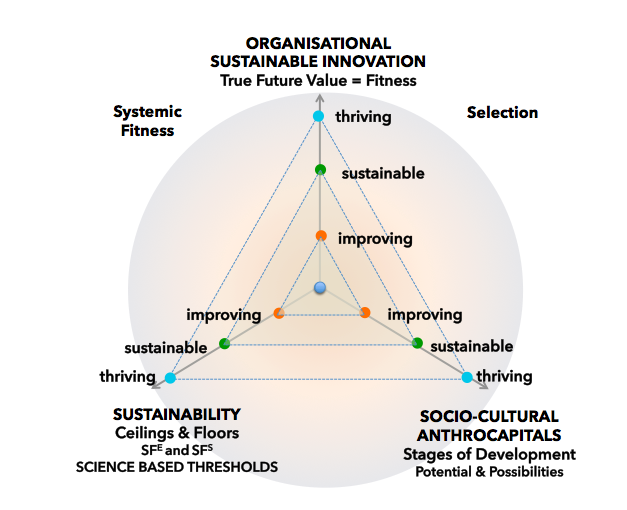

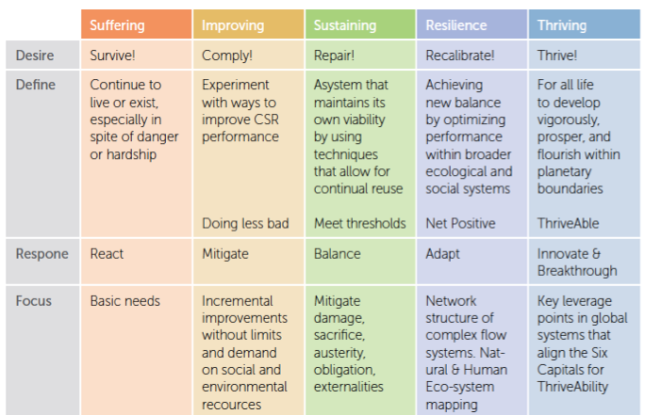

Diagram 3: Integral thinking and true materiality need a renewed focus on the purpose of the organization and connectedness to the economy we want to live in. Diagram 4: The strategy continuum to assess a company’s position in a world that needs to leapfrog from surviving to thriving (Source: A Leader’s Guide to ThriveAbility, page 18).

Diagram 4: The strategy continuum to assess a company’s position in a world that needs to leapfrog from surviving to thriving (Source: A Leader’s Guide to ThriveAbility, page 18).